Biggest Threats to Grizzly Bears (And How You Can Help Protect Them)

As the unfortunate passing of grizzly 399—known affectionately as the “Queens of the Tetons”—sent shockwaves through the national park/outdoors/wildlife community, this heartbreaking event also has the potential to change things for the better. But only if we act.

In the 21st century, grizzly bears in the continental United States continue to face several threats to their very existence. And without proper action, these threats will only increase, expand, and possibly eventually overwhelm the grizzly population.

Below, I’ve summarized the five currently biggest threats to grizzly bears in the lower 48 states, from urban development to climate change and habitat reduction. For each threat, I’ve provided one or more ways we can contribute to their survival.

A Brief History of Grizzly Bears in the Lower 48 States

Prehistory – 1800s

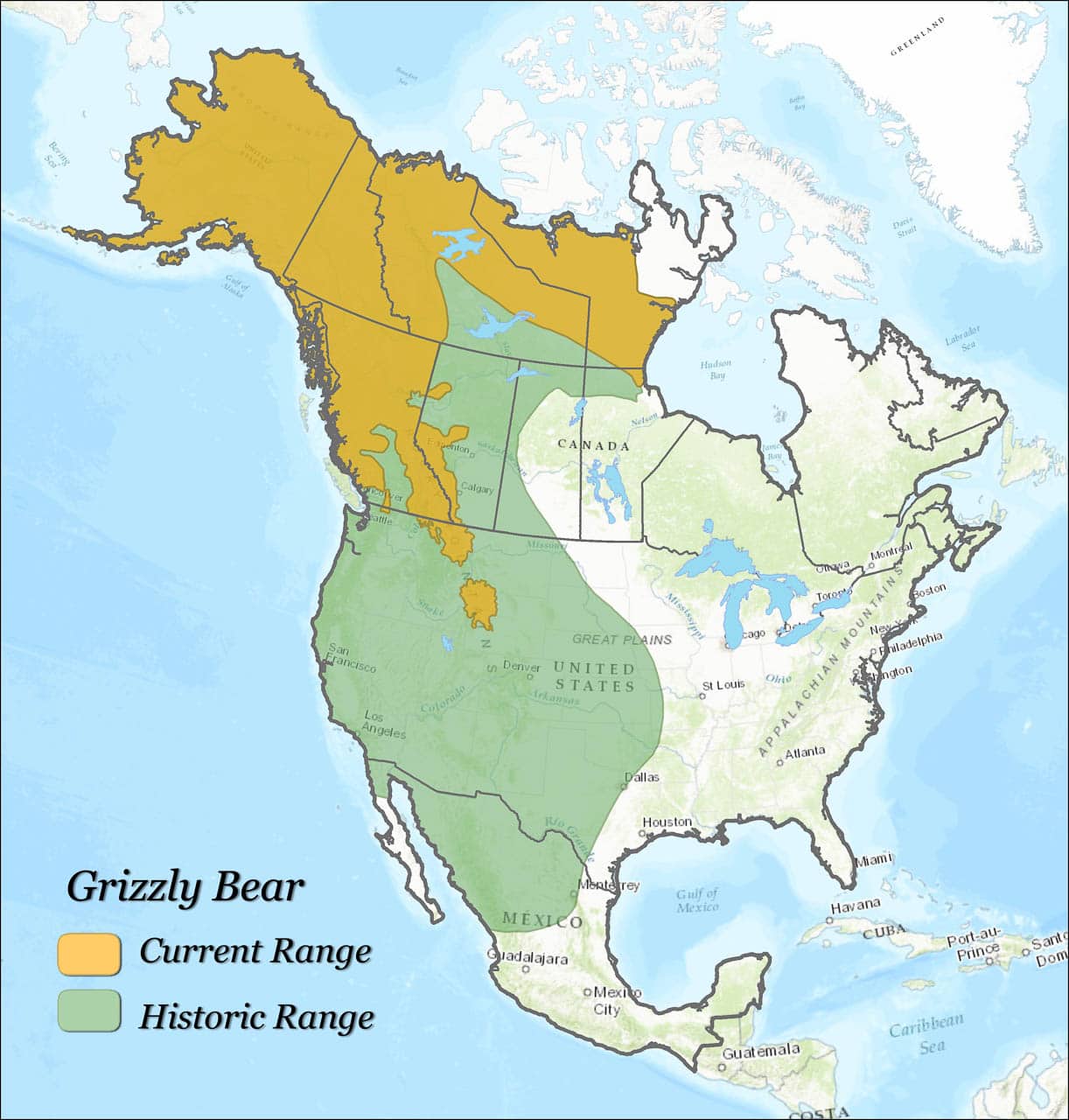

Just a few hundred years ago, an estimated 100,000 grizzlies roamed the North American continent, from the tundra of Alaska to the arid mountains of northern Mexico. Approximately half of them lived in what are now the lower 48 states of the United States.

For countless thousands of years, they dug for roots in the Rocky Mountains, fished for steelhead and salmon in the rivers of the Pacific Northwest, scavenged on carcasses in the Plains, foraged for berries in Alaska. Then, Euro-American settlers began traveling west, and everything changed.

1800s – early-1900s: Population Decimated

Halfway through the 20th century, there were only 700 to 800 wild grizzly bears left south of Canada and the species came perilously close to extinction in the lower 48 states. This spectacular population decline was due exclusively to human activity.

Settlers killed grizzlies to protect livestock or themselves, to harvest their fur, or simply for sport. Many killings were also the result of government-sponsored programs to eradicate them completely.

In addition to active extermination, grizzlies were also indirectly affected by western expansion.

Railroad tracks were laid, pioneer towns sprang up, forests were felled, rivers were dammed, ranches were established. Then came the automobile and the concrete development of cities.

The grizzlies’ habitat shrunk each year and became increasingly fragmented. Within just a few decades, they suddenly had to navigate railroads and highways, private gardens and expansive farmlands.

1975: Listed As a Threatened Species

The population of grizzlies plummeted to severely that, in 1975, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service listed the grizzly bear as a threatened species under the Endangered Species Act.

1993: Grizzly Bear Recovery Plan

In 1993, the Interagency Grizzly Bear Committee was established to create, implement, and oversee the Grizzly Bear Recovery Plan.

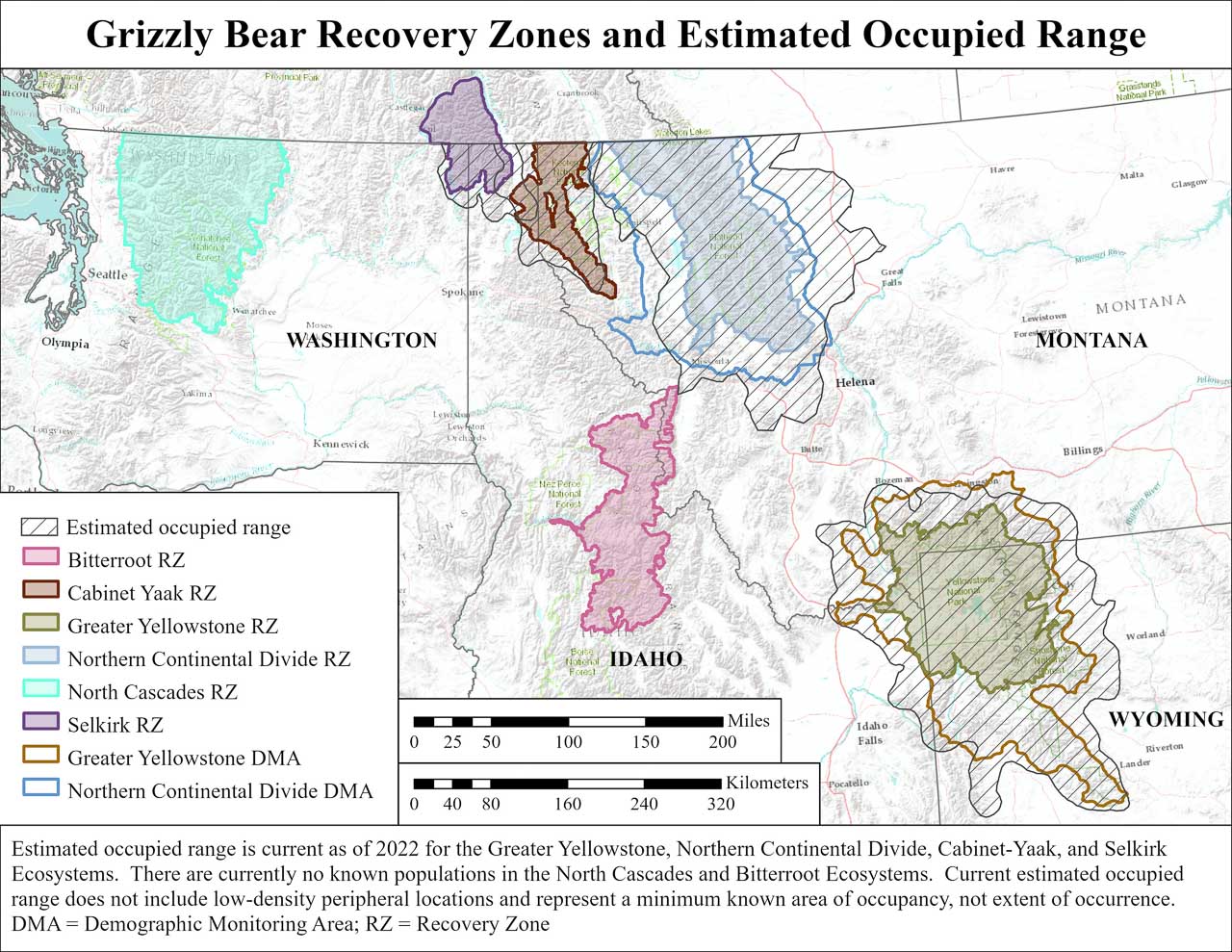

Within that plan, six suitable ecosystems are identified, each with a grizzly recovery zone in its center:

- Greater Yellowstone (GYE) in northwestern Wyoming, eastern Idaho and southwestern Montana

- Northern Continental Divide (NCDE) of north-central Montana, which encompasses Glacier National Park and the Bob Marshall Wilderness

- The Selkirks (SE) area of northern Idaho, northeast Washington and southeast British Columbia

- The Cabinet-Yaak (CYE) area of northwestern Montana and northern Idaho

- The Bitterroot (BE) in the Bitterroot Mountains of central Idaho and western Montana

- The North Cascades area of north-central Washington

Currently, there are just under 2,000 grizzly bears in the lower 48 states. Nearly all of those live in either the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem (700+) or the Northern Continental Divide Ecosystem (almost 1,100).

The remaining grizzlies are found in the Cabinet-Yaak Ecosystem (60) and the Selkirks Ecosystem (about 45).

There are no known grizzlies in the Bitterroot Mountains or the North Cascades, although both ecosystems are considered to be a potential recovery zone.

What this means is that the almost the entire grizzly population in the contiguous United States is currently confined to just two separate areas, centered respectively on Yellowstone and Glacier. Those are the only two regions that have a large and healthy population of grizzly bears.

Grizzly Bear Recovery Opposition and Challenges

Additionally, it must be mentioned that the Grizzly Bear Recovery Plan has faced serious opposition from states (Idaho, Wyoming, and Montana), almost from the time of its inception.

For example, as early as 2001, a Bitterroot Mountains reintroduction plan was vehemently opposed and was never actually implemented.

In the following couple of decades, Yellowstone grizzlies got delisted twice, followed by being listed again after appeals from environmental and tribal groups. Grizzlies in northern Montana, as well as in other recovery zones, are the subject of the same discussions—or, rather, disagreements.

The same goes for plans to reintroduce grizzly bears to the North Cascades, which have been in the works since 2014. In April of 2024, a final decision was made to (finally) restore grizzlies to their historic range in the North Cascades.

At this time, grizzly bears are still or, in some cases, again, protected as a threatened species.

The timeline of grizzly bear recovery is as long as it is complicated. You can see it here.

This is all to say that grizzly bear conservation is extremely complex. Successful conservation requires cooperation and partnerships between numerous stakeholders, including the Interagency Grizzly Bear Committee, Native American Tribes, federal agencies, state wildlife agencies, and other organizations.

And that brings us to the biggest threats faced by grizzly bears in our modern 21st-century world.

5 Biggest Threats to Grizzly Bears (And How You Can Help)

Even though the number of grizzlies in the lower 48 states has rebounded, there remain several major threats to their future.

1. Human Food Conditioning

“A fed bear is a dead bear.” One of the biggest problems faced by wildlife management is grizzlies becoming conditioned to human foods.

This problem exists both in national parks and forests, and in developed areas. Visitors leaving out food at their campsites, people not cleaning up picnic areas, locals not properly storing pet foods or securing garbage,… this can all attract bears, who are always looking for an easy meal.

As a result, they’ll begin associating humans with food. When that happens, a food-conditioned bear becomes dangerous, as it will continue to approach humans, campgrounds, and homes, searching for something to eat. Many of these bears, if hazing them hasn’t been effective, are subsequently killed.

What You Can Do

In theory, preventing grizzly bears from associating humans with food is pretty straightforward. All it requires is that everyone securely stores or locks up anything that may attract a bear. This includes food, toiletries, garbage, pet foods, and livestock feed.

So, visitors should always keep a clean campsite or picnic area. Put away anything that has a scent in bear-proof locker. Don’t leave leftovers out on the table. Put garbage in bear-proof trash bins.

Similarly, people living in bear country should bear-proof their homes, yards, and fields. Secure all attracts. Use approved bear-proof trash containers. Install electric fences around things like chicken coops, beehives, compost piles, and fruit trees.

Besides adhering to these best practices, you can also help reduce food-conditioning by grizzlies by supporting initiatives like Jackson Hole Bear Solutions and Bear Wise Jackson Hole.

2. Urban Development

Another enormous issue facing grizzly bears is increasing urban development in their historical range, particularly in places like Montana’s Mission Valley and the Jackson area in Wyoming.

Grizzlies need room to roam. And a lot of it. In fact, grizzly bears cover huge distances in search of sustenance, a place to den for winter, and a mate, and each grizzly needs an area of hundreds of square miles.

Developed areas in Montana and Wyoming continue to expand, whether it’s (tourist) towns or farmlands.

Ironically, it’s often the grizzlies that many visitors come to see, which in turn creates more demand for accommodations, amenities, and outdoor recreation. Vehicle traffic continues to increase, which also increases the risk of vehicle-bear collisions.

Additionally, development also often results in a more fragmented habitat. Separate populations of grizzlies can’t exchange genes, which, especially for small populations like those in the Selkirks and Cabinet-Yaak area in Idaho, may eventually lead to inbreeding and, even worse, regional extinction.

“With every new house and road built on land that was once home to grizzlies, the species’ chance of establishing habitat connections and regaining historic range dwindles,” the Vital Ground Foundation says.

What You Can Do

While a single individual, unless they’re a powerful politician, will never be able to stop urban development in historic grizzly habitats, there are some things you can do to help grizzlies survive.

The most practical action is simply to be extremely cautious when driving through grizzly habitat. Always adhere to speed limits, avoid driving in the dark, and be vigilant on sections of road with low visibility, such as undulating hills, canyons, and densely forested areas.

Additionally, constructions like wildlife overpasses and underpasses, along with proper fencing, have proven to be exceptionally successful at reducing traffic-related wildlife mortality.

Consider supporting organizations like the Jackson Hole Wildlife Foundation to help create a landscape where wildlife and people can co-exist.

3. Habitat Reduction

The continued reduction of suitable grizzly bear habitat is the direct result of increased development. As I said above, grizzlies need a vast area to allow them to thrive.

Nowadays, the historic range of grizzlies is a patchwork of villages, towns, and cities, industrial areas, sprawling farmlands, and parks. All of those are interconnected by thousands of miles of roads, highways, and railroad tracks.

The result of this is a sheer fragmentation of grizzly habitat, a lack of secure territory without any chance of human interaction, and a dire need for safe corridors that link those fragmented areas.

What You Can Do

The best way you can help restore grizzly bear habitat, as well as help connect those habitats, is by supporting the Vital Ground Foundation.

It’s a fantastic non-profit organization that envisions “a permanently connected landscape that ensures the long-term survival of grizzlies and the many native species that share their range. By connecting public land strongholds with protected private lands, Vital Ground is the only land trust dedicated to large-landscape conservation for the benefit of grizzly bears, other wildlife and people.”

Another great organization that works to protect grizzly habitat, create connective corridors, and promote coexistence in northern Montana is the Glacier-Two Medicine Alliance.

4. Human-Bear Conflicts

As development increases and grizzly habitat becomes more fragmented, the risk of human-bear conflicts continues to climb.

These conflicts can occur in many forms, from vehicle collisions and property damage to illegal hunting, food-conditioned bears in towns, and bears looking for food in fields and farms.

In recent years, human-bear conflicts have risen dramatically, due to both higher grizzly bear numbers and the increased popularity of parks, as well as the expansion of the human population in certain areas in Montana and Wyoming.

More bears, more people, more development,… Without proper management and measures to address potential “hotspots,” conflicts are all but inevitable.

What You Can Do

The solutions to reduce human-bear conflicts are in line with those for food-conditioning, urban development, and habitat reduction. After all, these conflicts are the very result of those three issues.

Help prevent bears from becoming food-conditioned by properly securing attractants, at campsites, in picnic areas, at your farm or ranch, or in your own backyard.

When driving through grizzly habitat, adhere to the speed limit, avoid driving at night, and be cautious on hills or around bends in the road.

Support organizations that advocate for wildlife overpasses and corridors, and strive to reduce human-bear conflicts, whether it’s in parks or in towns.

Excellent examples are all the organizations I already mentioned earlier: Jackson Hole Bear Solutions, Bear Wise Jackson Hole, the Jackson Hole Wildlife Foundation, the Glacier-Two Medicine Alliance, and the Vital Ground Foundation.

5. Climate Change

Growing evidence indicates that climate change will only pose more challenges to grizzly bears in the future. Rising temperatures mean shorter winters, which means bears will spend less time in their den and emerge sooner.

Subsequently, they’ll spend more time looking for food, which may or may not be available when they emerge from hibernation.

Moreover, climate change doesn’t only impact the grizzlies themselves, but also some of their traditional food sources.

For example, according to Wyoming Wildlife Advocates, whitebark pines are functionally extinct in the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem, so bears no longer have access to their high-energy nuts.

Invasive lake trout, which live in deeper water, have significantly reduced native cutthroat trout populations. And army cutworm moths, a very popular grizzly food, rely on high-altitude plants that may suffer from shorter winters and warmer summers.

All of this makes it a realistic prediction that grizzlies will come down to urban areas to find food, whether it’s improperly secured trash, pet food, livestock feed, or even the pets and livestock themselves.

This, of course, will once again result in a higher potential for negative human-bear interactions.

What You Can Do

The climate is changing as we speak, which, as things stand in the world, is something that is all but irreversible. The issues described above will happen. So what can we do to help grizzly bears navigate this increasingly challenging future world?

The answer lies in the things I’ve talked about above: best practices to reduce human-bear conflicts, building safe corridors and road crossings so bears can move more freely and safely, and supporting grizzly conservation organizations.

Consider donating to the Vital Ground Foundation, Jackson Hole Wildlife Foundation, and/or Wyoming Wildlife Advocates.

Grizzly Bear Conservation Organizations Mentioned in this Article

- Jackson Hole Bear Solutions

- Jackson Hole Wildlife Foundation (Bear Wise Jackson Hole)

- Wyoming Wildlife Advocates

- Vital Ground Foundation

- Glacier-Two Medicine Alliance

Thank you for reading this article about threats to grizzly bears and possible solutions. Please consider supporting the organizations featured above and ensuring the future of grizzlies in the lower 48 states.