13 National Park Service Sites & Historic Trails That Preserve Latino / Hispanic Heritage

Decades, even centuries, before the United States gained independence, Hispanic and Latinx people were shaping the history and culture of present-day North America. Today, this wealth of Hispanic heritage is visible at numerous National Park Service sites, from California and New Mexico to Florida and Massachusetts.

The Hispanic heritage preserved in these national parks, monuments, memorials and recreation areas encompasses many historical and cultural aspects. These sites are as diverse as the Latino or Hispanic communities and nationalities themselves.

10 National Parks, Monuments & More That Preserve Latino / Hispanic Heritage

From early Spanish explorers, conquistadors and Franciscan priests to civil rights leaders and immigrant factory workers, countless tales can be told about Latino and Hispanic people in America.

These national parks with Hispanic heritage interpret the stories of Latino and Hispanic Americans, from the past through the present.

Cabrillo National Monument, California

Set at the tip of the Point Loma Peninsula, just west of the San Diego city center, Cabrillo National Monument is the only National Park Service site in San Diego.

This monument commemorates the spot in San Diego Bay where, in late-September 1542, Juan Rodriquez Cabrillo stepped onto the west coast of what would later become the United States.

He was the first European to set foot on the North American west coast.

Established in 1913, Cabrillo National Monument is home to a statue of Cabrillo, which overlooks the bay where he anchored his ship. You can learn all about the Spanish explorer and conquistador’s life and the times he lived in at the Visitor Center.

This fascinating national park in San Diego also offers great views of the harbor and skyline of San Diego, while on clear days, you can see as far as Tijuana and the Coronado Islands in Mexico.

More information: https://www.nps.gov/cabr/index.htm

Santa Monica Mountains National Recreation Area, California

Situated in the greater Los Angeles region, the Santa Monica Mountains National Recreation Area is a fantastic place to escape the urban sprawl of L.A.

This huge National Park Service site preserves numerous places with rich Hispanic heritage. The largest urban national park in the United States, the Santa Monica Mountains extend from the famous beaches of Malibu to arid hills and historic farmlands.

More than 500 miles of trails allow visitors to immerse themselves in this amazing natural and cultural landscape.

Hispanic history in the Santa Monica Mountains begins in the 1700’s. In that century, Spanish missionaries attempted to convert Native Americans to Christianity and employ them as workers to build missions.

Additionally, the Spanish government in Mexico also offered land grants to Spanish soldiers and Mexicans in Alta (Upper) California. They established “ranchos” to raise livestock and grow crops, becoming “rancheros.”

These original Spanish ranchers brought with them many animals and foods that didn’t previously exist in California. This included horses, sheep, cattle and wheat.

After California became a part of the United States in 1848, a lot of those Mexican ranchers and homesteaders moved out of the region. They left behind some of the Hispanic heritage at this National Park Service site that is still visible today.

Later, the Homestead Act of 1862, triggered another immigration wave from Mexico to the Santa Monica Mountains, as well as from many other places.

What is now Thousand Oaks, Topanga, Westlake Village and Malibu, along with numerous other locations in southern California, were once places where Mexicans raised cattle and grew crops and vegetables.

More information: https://www.nps.gov/samo/index.htm

Tumacácori National Historical Park, Arizona

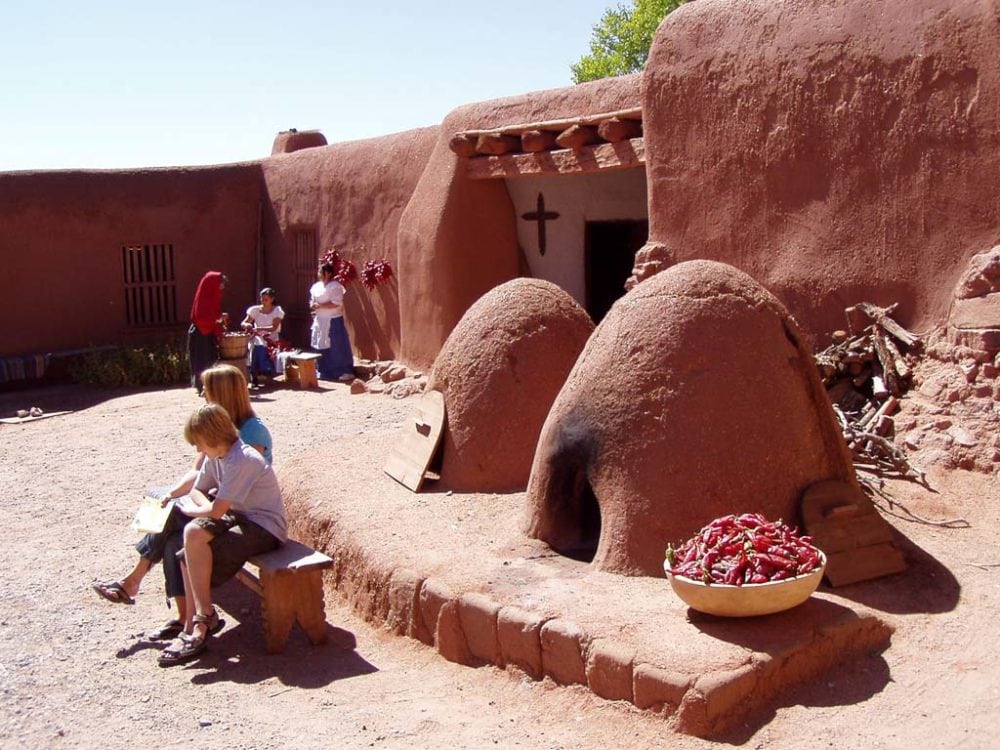

Situated at a crossroads of cultures in Arizona’s Santa Cruz River valley, Tumacácori is where native O’odham, Yaqui and Apache met, interacted and co-existed with Spanish soldiers, settlers and missionaries. These encounters were often cooperative, while some were more violent.

The story of Tumacácori takes place over countless centuries, from the millennia during which Native Americans lived here to the arrival of the Spanish in the 17th century and to this day.

It involves a diversity of peoples from different continents. Rather than archaeological, natural or architectural, this is very much a human story.

Tumacácori National Historical Park is a fantastic place to immerse yourself in the lives, struggles and joys of the people who once called this area home, or those who just passed through on their way to other destinations.

Learn about the cultures of local O’odham, Yaqui and Apache people and see what role women played at Tumacácori.

Discover how Jesuit priests, Spanish soldiers and Franciscan missionaries, who established presidios and missions in the Southwest, changed the area and local way of life forever.

In addition to Christianity and European customs, as well as disease, the Spanish also brought livestock, horses, metal tools and fruit trees to Arizona.

After Mexico gained independence from Spain, things changed completely once again for the people of Tumacácori, resulting in an exodus from the area.

To protect the historic Tumacácori Mission and its buildings against decay, looting and vandalism, President Theodore Roosevelt designated it a national monument in 1908.

You can watch a wonderful film about the history of Tumacácori on the park’s website.

Additionally, Tumacácori National Historical Park is part of the Juan Bautista de Anza National Historic Trail (see below), which links numerous Hispanic heritage sites across the Southwest.

More information: https://www.nps.gov/tuma/index.htm

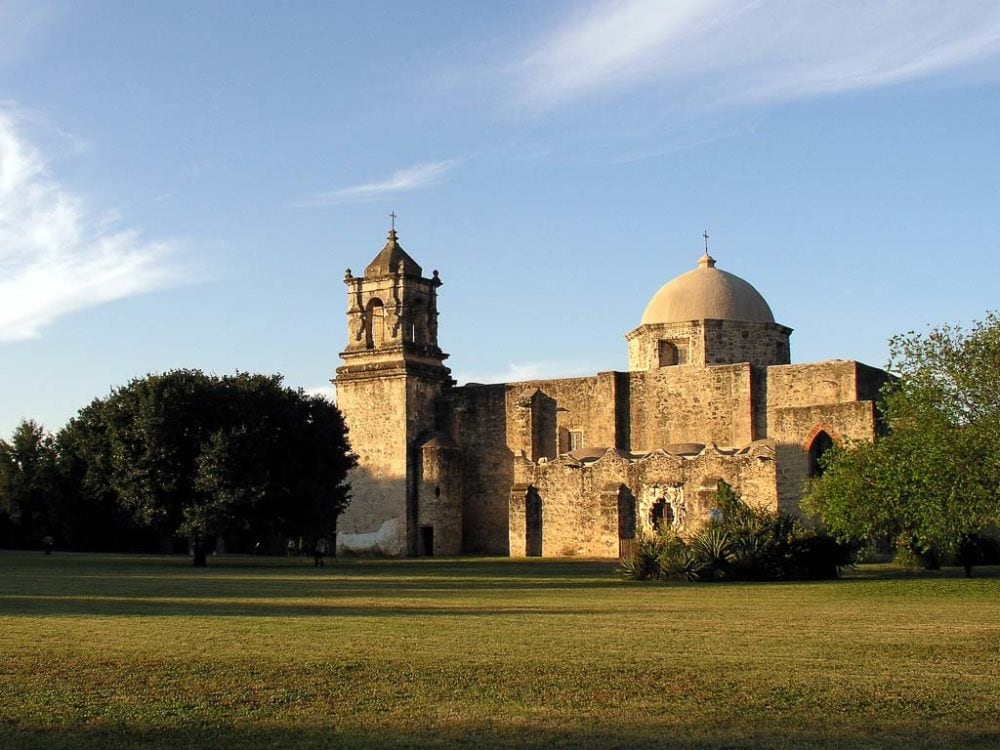

San Antonio Missions National Historical Park, Texas

A collection of outposts in San Antonio, Texas, the San Antonio Missions were first established by Spanish Catholics with the purpose of spreading Christianity among Native Americans.

Founded in the late-17th and early-18th centuries, they were part of a much larger system of colonization that extended across the Spanish Southwest.

After 10,000 years without any major foreign threats, the local population found itself under attack on various fronts in the first decades of the 1700’s.

Bands of Apaches carried out raids from the north, while lethal diseases spread from Mexico. On top of that, persistent drought resulted in a food crisis.

The Spanish missionaries took advantage of the situation by offering Native Americans refuge in the missions. Survival was possible by giving up their traditional lifestyle, swearing fealty to a faraway king and becoming Christian.

Over time, a diverse population of people lived and worked at the San Antonio Missions, along with the Native Americans. A minority were people coming straight from Spain, usually missionaries and soldiers. Others were originally from New Spain, or present-day Mexico.

The majority of the missions’ population, however, were mixed-race people. They had Spanish names, but were a mix of Spanish and Native American. They eventually became the area’s artisans, craftspeople, traders, leaders and officials. These people were the first of what is now the vibrant Latinx community in Texas.

The four missions that make up the San Antonio Missions National Historical Park are, from north to south, Mission Concepción, Mission San Jose, Mission San Juan and Mission Espada.

More information: https://www.nps.gov/saan/index.htm

El Morro National Monument, New Mexico

The commanding sandstone formation known as El Morro has guided people for many centuries. More than 700 years ago, Ancestral Puebloans built pueblos on El Morro and carved symbols and images into the rock.

Throughout the decades and centuries, a waterhole at the cliff’s base made it a popular stopping point for weary and thirsty travelers.

In the 16th century, Spanish expeditions made their way into the area in search of gold and silver and to establish missions. This resulted in the first official historic record of El Morro.

A particularly significant exploration was the one by Don Juan de Onate in 1598. Bringing 400 colonists and 10 Franciscans into what is now New Mexico, he effectively founded the first European colony in New Mexico.

However, challenging winter weather, food scarcity and the remoteness of the location made the colony unsustainable. While he returned from his expeditions, someone inscribed his name at El Morro on April 16, 1605—the first European inscription at El Morro.

Soon after, though, traveling soldiers, priests and governors added their own inscriptions while traveling to the western pueblos. Although they’re short and small notes on rock, the many inscriptions at El Morro National Monument provide a valuable insight into Hispanic history in New Mexico.

“Here, on the frontier far from Santa Fe, records of passage—a name and a date attached to the phrase paso por aqui—are incised alongside accounts of battles to avenge the ambush of a detachment or the killing of a priest.”

– National Park Service

More information: https://www.nps.gov/elmo/index.htm

Blackstone River Valley National Historical Park, Rhode Island and Massachusetts

The birthplace of the American Industrial Revolution, the Blackstone River Valley in Rhode Island and Massachusetts is the place where the United States moved from “Farm to Factory.”

The National Park Service notes that “America’s first textile mill could have been built along practically any river on the eastern seaboard, but in 1790 the forces of capital, ingenuity, mechanical know-how and skilled labor came together at Pawtucket, Rhode Island, where the Blackstone River provided the power that kicked off America’s drive to industrialization.”

Now known as the Slater Mill, this mill was hugely successful, inspiring other entrepreneurs to construct their own mills. First, they were situated along the Blackstone River, later expanding into the rest of New England.

As the size and number of the mills grew, there was a constant need for new workers. This sparked various waves of immigrants. The first wave were French Canadians, particularly during the Civil War in the mid-19th century.

Irish, Italians, Swedes, Portuguese and Polish arrived in the Blackstone River Valley around the turn of the 20th century.

During the 1970’s, people from the Dominican Republic, Colombia, Guatemala and other Latin American countries came to work in the valley’s factories.

Each nationality brought its own culture and heritage with it, creating a vibrant cultural melting pot. Nowadays, the Blackstone River Valley National Heritage Corridor still has a significant Hispanic community.

More information: https://www.nps.gov/blrv/index.htm

César E. Chávez National Monument, California

Arguably the most significant Latino leader in the United States in the 20th century, César E. Chávez spearheaded the farm workers movement, leading to the establishment of America’s first permanent agricultural union.

He founded the National Farm Workers Association in 1962, which later became the United Farm Workers of America (UFW).

Also led by other Latinx people, particularly Dolores Huerta and Larry Itliong, the movement was supported by millions of Americans and was an unequivocal success.

Inspiring people across the country through non-violent protest actions, including boycotts and personal fasting, César E. Chávez “brought sustained international attention to the plight of U.S. farm workers, and secured for them higher wages and safer working conditions.”

From its roots as a farm workers union, the UWF grew to become a nation-wide voice for the poor and disenfranchised.

His legacy, which changed work in the United States forever, also includes the passage of the 1975 Agricultural Labor Relations Act in California, the very first law in the country that recognized the collective bargaining rights of farm workers.

More information: https://www.nps.gov/cech/index.htm

Pecos National Historical Park, New Mexico

For many thousands of years, the Pecos Valley in New Mexico has been the home of many different peoples.

“Pueblo and Plains Indians, Spanish conquerors and missionaries, Mexican and Anglo armies, Santa Fe Trail settlers and adventurers, tourists on the railroad, Route 66 and Interstate 25… the Pecos Valley has long been a backdrop that invites contemplation about where our civilization comes from and where it is going.”

– National Park Service

Pecos National Historical Park sits in a verdant valley near the Sangre de Cristo Mountains, a fertile area that allowed for the growing of crops. Native communities expanded and grew into dozens of pueblos, which ultimately got consolidated into the large Pecos Pueblo by 1450.

The 17th century marked the arrival of the Spanish. Pecos Pueblo had become well-known throughout the region by then, attracting Spanish soldiers looking for resources and missionaries looking to spread Catholicism.

The Spanish started founding a colony and Franciscan missions in the Pecos Valley. This was their way to establish complete control over the Puebloans, including control over the local economy and belief systems.

The Puebloans, however, didn’t agree with this approach at all. In 1680, they banded together and started what effectively was the very first American Revolution.

Led by Po’pay from the San Juan Pueblo, the Pueblo Revolt was successful. It was the only time in history that Native Americans successfully expelled European invaders.

The Spanish came back with a vengeance in 1692, though, finding little resistance from a Pecos Pueblo population suffering from European diseases and Comanche raids. Numerous missions were re-established near the area’s pueblos.

Later on, the legendary Santa Fe Trail opened in 1821 after Mexico became independent from Spain, passing right through Pecos Pueblo and its Spanish missions. This added yet another layer of historic importance to this fascinating place.

More information: https://www.nps.gov/peco/index.htm

Castillo de San Marcos National Monument, Florida

Erected by the Spanish in St. Augustine in 1672, the Castillo de San Marcos defended the coast of Florida and their important Atlantic trade route. It was one of the largest European fortresses in the “New World.”

This massive coastal stronghold is the oldest masonry fortification in the United States. Preserved as a national monument, this is where you can explore 450 years of cultural interactions.

As they did elsewhere in North America, the Spanish also tried to Christianize Native American people in St. Augustine, including the Apalachee and Caloosa. Up to 80% of the native population, however, was gone just a few decades later.

Additionally, Castillo de San Marcos also played a significant role in the Atlantic slave trade. Built partially by Black Spanish slaves, the fortress later was among the first points of entry of British African slaves into Spain’s North American territories.

The Spaniards, however, freed them, which resulted in the first legally established free African settlement in North America—Fort Mose in 1738.

More information: https://www.nps.gov/casa/index.htm

Golden Gate National Recreation Area, California

The Golden Gate National Recreation Area in San Francisco is one of the most-visited National Park Service sites, drawing in more than 12 million visitors each year. The area encompasses several San Francisco landmarks, including such famous ones as Alcatraz and the Golden Gate Bridge.

It’s also home to the Presidio of San Francisco, established by Juan Bautista de Anza in 1776. (see Juan Bautista de Anza National Historic Trail below). This was the final destination of that historic expedition from Mexico to what is now San Francisco.

“Presidios” were Spanish-Mexican military garrisons that housed a small contingent of soldiers. Usually, they were constructed close a mission, protecting the expanding territory of Spain in the Americas.

Along with its mission, the Presidio of San Francisco was the northernmost outpost of the Spanish Empire in North America, which stretched south across modern-day Mexico.

Throughout its history, the Presidio served as an army post for three different countries—Spain, Mexico and the United States.

It actually was a U.S. Army post until as recently as 1994, when it became a part of the Golden Gate National Recreation Area and a National Park Service site preserving important Hispanic heritage.

More information: https://www.nps.gov/prsf/index.htm

More National Park Service Sites That Preserve Latinx and Hispanic Heritage Sites

- Palo Alto Battlefield National Historical Park, Texas – National historical park that preserves U.S. and Hispanic heritage, particularly the area where United States and Mexican troops clashed in 1846. The battle of the Palo Alto prairie was the first in the two-year U.S.-Mexican War that ended up changing the map of North America.

- Chamizal National Memorial, Texas – The grounds of Chamizal National Memorial commemorate the Chamizal Convention of 1963, a peaceful settlement of a 100-year border dispute between the United States and Mexico

- San Juan National Historical Park, Puerto Rico – UNESCO World Heritage Site that preserves the fortifications of the Spanish-founded city of San Juan in Puerto Rico, which protected this small island for centuries.

- Valles Caldera National Preserve, New Mexico – Area of previous Spanish and Mexican settlements in the present-day American Southwest, encapsulating the social and political changes that happened when the United States annexed the region.

- National Mall and Memorial Parks, Washington, D.C. – General Simón Bolívar Memorial, Bernardo de Gálvez Memorial, Benito Pablo Juárez Memorial and Cuban American Friendship Urn

3 National Historic Trails Lined With Hispanic Heritage Sites

In addition to the national parks and other sites above, there are also two national historic trails that preserve Hispanic history.

These trails follow and retrace important historical routes in the American Southwest, linking numerous individual sites, monuments and parks related to Hispanic heritage in America.

El Camino Real de los Tejas National Historic Trail, Texas and Louisiana

During the Spanish colonial period, several caminos reales, or “royal roads”, connected remote areas of the Spanish Empire in North America to Mexico City.

One such road was El Camino Real de los Tejas, which followed a series of indigenous trails and trade routes from Mexico City across modern-day Texas and into northwestern Louisiana. This road served as the main overland route for the Spanish colonization of Texas.

Its name comes from a prominent group of Caddo Indians, to whom the Spanish referred as the Tejas, which in its turn came from a Caddo word for “ally” or “friend.”

To make a rather long story short, El Camino Real de los Tejas played a pivotal role in the creation and history of the present-day state of Texas. Its rich history involves disputes between French and Spanish colonizers, as well as with the native population.

In fact, the Caddo people strongly opposed the presence of the Spanish. Often, it were the Native Americans who dictated the conditions of Spanish settlement in eastern Texas, rather than the other way around.

The establishment of numerous large ranches along the Rio Grande south of Laredo is also a result of this historic route—ranchers used to drive cattle along the El Camino Real de los Tejas.

Additionally, the route was later also frequently used by Anglo-American settlers in Texas, which ultimately led to revolt against Mexico, and the use of the El Camino Real by both armies.

After the United States annexed Texas in 1845, the original route lost most of its importance.

More information: https://www.nps.gov/elte/index.htm

El Camino Real de Tierra Adentro National Historic Trail, New Mexico

In the Spanish colonial period in North America, one single road connected New Mexico to the rest of the world. This thoroughfare started just north of Santa Fe and descended the valley of the Rio Grande. In El Paso, it ran through a natural gateway before continuing across New Spain to Mexico City.

This 1,200-mile road was called El Camino Real de Tierra Adentro—“royal road” or “king’s highway.” It followed ancient Native American trade corridors and footpaths, which also, already, linked the ancient cultures of Mexico to those in the southwestern United States.

According to the National Park Service, “it was the oldest of the great highways heading north.” After more segments were added during the 1500’s, at one point, it was North America’s longest road.

Nowadays, people in both Mexico and the United States recognize El Camino Real de Tierra Adentro as “a timeless route of trade and cultural exchange, with a complicated legacy of 300 years of conflict, cooperation, and cultural exchange between a variety of peoples.”

More information: https://www.nps.gov/elca/learn/historyculture/index.htm

Juan Bautista de Anza National Historic Trail, Arizona and California

A legendary Spanish explorer, Juan Bautista de Anza opened up the overland route from Mexico to California during a 1775-76 expedition.

The Juan Bautista de Anza National Historic Trail follows the route taken by the Spanish colonists from Sonora in Mexico, which was then called New Spain, through Arizona to California. They ultimate stopped and settled in Alta California, establishing the mission and presidio in what is now San Francisco.

The expedition consisted of a wide variety of people with African, Native American and Hispanic heritage. The group of over 240 colonists included 30 soldiers and their wives, as well as more than 100 children.

Extending some 1,200 miles, the Juan Bautista de Anza National Historic Trail links many dozens of sites that preserve Hispanic heritage.

Major sites in Arizona include Tumacácori National Historical Park (see above), Saguaro National Park and Casa Grande National Monument.

In California, the trail runs past or through places like Anza-Borrego Desert State Park, El Pueblo de Los Angeles Historical Monument, Mission San Luis Obispo, San Juan Bautista State Historic Park, De Anza Historical Park and the Presidio of San Francisco, which was the expedition’s endpoint.

More information: https://www.nps.gov/juba/index.htm